THE BORDER REPORT

The case of an accused Sinaloan drug lord grows more and more curious each week and I like it because it's messy. It illustrates nicely just how little the United States and Mexico actually cooperate on cross-border investigations. Three back and forth phone calls between the two countries would clear most of this case up – and it'll never happen.

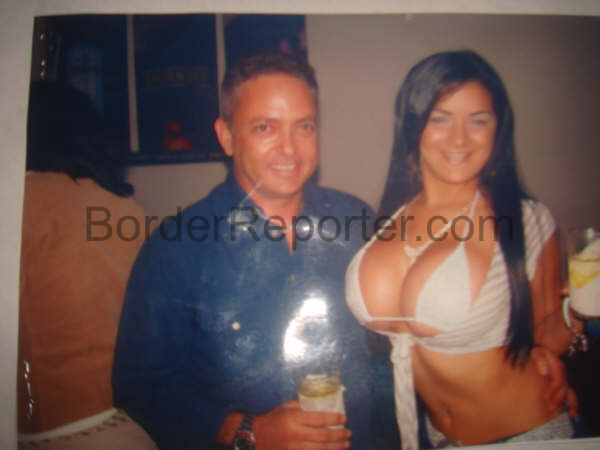

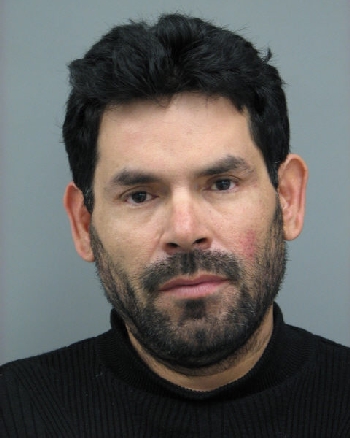

Depending on whom you ask, Antonio Frausto Ocampo is either a hapless tourist caught up in the fiascoes of his drug trafficking nephew or a powerful drug lord working for the Sinaloans. He either executed a photojournalist in a small town on the Sinaloa coast in 2004 or another man bearing his same name did so. He either killed a man who had ripped him off in Phoenix fourteen years ago or he didn't. Or the guy deserved it for not shooting first.

He either killed his wife's cousin or she doesn't have a cousin. You have DEA agents who don't speak Spanish trying to listen to wiretaps and defense attorneys who can't seem to decide what their client's name is. Meanwhile, the federal judge sounds about to ready to give up on the whole case.

His name is either Antonio Frausto Ocampo or it is Antonio Frausto Díaz. And it's not merely the Feds who are confused.

Frausto's lawyer, Carlos Monzón, and the accused man's wife can't seem to agree either. Consider this February 27 court hearing where Monzón is addressing the court:

" ... the individual that they (the government) claim is Mr. Frausto, that is a part of the Sinaloa cartel, that individual was arrested in June 2008 and is and remains in custody of the Mexican government. However, Mr. Sigler was adamant, and he continued arguing to the court that Mr. Frausto Díaz, my client, and Mr. Antonio Frausto Ocampo, were one and the same individual." Sigler is the prosecutor in the case.

Frausto Ocampo isn't his client, the lawyer argued. Frausto Díaz is.

The same day, Monzón asked Frausto's wife, Asylvia Acosta on the stand:

"Is your husband a trigger person for the Sinaloa Cartel?"

"No," she said.

"Is your husband's real name Antonio Frausto Ocampo?"

"Yes," she replied.

Monzón didn't return four phone calls and emails today inquiring about the case, but has argued in court that the only reason Frausto has left and come back to the U.S. so often is because he was visiting a doctor in Mexico. The United States has argued that the reason he crossed back and forth as often as he did is because he was running 75 pounds of cocaine and meth every day for the Sinaloans since 2002.

Last Thursday, an exasperated judge

told Monzón, "I frankly don't know who your client is."

Frausto, 45, was arrested last January by the DEA in Omaha, Nebraska, accused of trying to sell some of the purest methamphetamine the Midwest had ever seen.

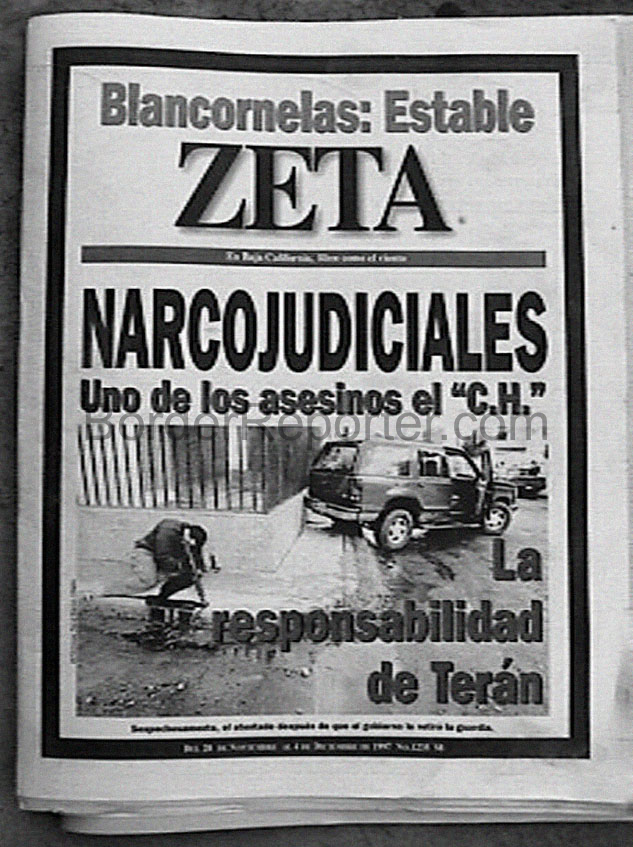

In 2004, he was fingered in the murder of a photojournalist in Escuinapa, Sinaloa, a town of 50,000 people south of Mazatlán near the border with Nayarit. A week before that hit (and you can read the full account

here), he was accused of shooting a doctor's wife in the arm when the doctor refused to treat a family member. Two weeks ago, the Sinaloa Attorney General's Office announced that an arrest warrant still exists for Frausto Ocampo in Sinaloa. State prosecutors won't reveal what the charge is, but said it is a firearms related felony committed in Escuinapa.

The U.S. still hasn't contacted Mexican authorities to inquire into the murder on that side of the border, a prosecutor said.

Then there's the Phoenix murders, which Monzón also has denied his client was involved in.

According to the 100-page report, in 1995, Frausto was at a party near Indian School Road in Maryvale, Phoenix's Culiacáncito, when a shooting went down ...

PHOENIX, 1995

When the cops arrived, the blue Oldsmobile was crumpled over a broken fire hydrant, stuck in reverse. Its windows were shot out, a body slumped on the driver’s side, three bullets, one in the head. Still breathing. He’d die later at the hospital.

Cops start piecing together what happened, the “shots fired” calls in the neighborhood, the red Jeep and the black pickup with the KC Lights on the roof splitting the scene. The victim was identified as Jaime Aispuro Corral.

Two days later, the dead man's cousin walks in to the police station, wanting to talk. There was a party in an alley between two apartment complexes. Men drinking, a couple musicians with a guitar and an accordion. He had stayed in the Oldsmobile, Jaime walked over alone, he tells the cops.

“He went over there and he talked to someone. He was on his way back and we came. There was some guy over there that had a rifle but he was – I heard him ask a friend of his for the keys to the truck and he didn’t want to give it to him so he put the rifle on him. I told him, let’s go, what are we doing here. So then he said why are you leaving. That’s all he said right. But I didn’t see, well there were tables like this and it was dark. There is no light on that street and he put the car in reverse to leave and he had just gone this way when he was coming with his hand like –. I don’t even know where he got hit because – with the gunshot. I tried to get him out of the car because I just saw him go like this and he didn’t push me or anything," he said.

Jaime slumped when the shots started, the cousin stepped out of the car. He felt a bullet whine past his head, felt like it parted hair.

He ran, jumping a fence, then stopped and looked back. By now, the shooter’s using the black truck to push the car out of his way. It had license plates from Chihuahua, he remembered.

He came back days later, this time remembering the shooter's name, Antonio Frausto.

Ten days pass, a woman walks in, she knows who the shooter is, she says.

She tells the cops that his name was Antonio Frausto. She believed he had the initials A.F.C. tattooed on his forearm. He lived north of Indian School Road. He dealt in cocaine in methammphetaime, she told the cops. He came from Mexico. Usually drove around town in a brown Mustang 5.0.

Five days later, the woman looks through the cops’ mugshots. She stopped at the third photo. Frausto. “That’s him,” she said. “I cannot be mistaken. That’s him.”

Frausto had been looking for Jaime. Jaime had fucked up a friend, she says.

Later, she tells the cops he always boasted he would never be caught. He could blend into a crowd anywhere.

The woman tells them about another murder, Frausto’s wife’s cousin. He killed the man over a drug deal at Central and Sunland and dumped the body in the East Valley, she says.

Eight years would pass before the investigation would carry on.

LOS ANGELES 2003

In 2003, the police interviewed another source, Frausto's brother-in-law, Jose Acosta Meza. He's doing time in L.A. County Jail when police interview him about Frausto. And he begins to talk.

Frausto was drunk and upset that night, Aispuro owed him on a drug deal. Aispuro and his cousin walked up to Frausto together and Aispuro's cousin pulled a gun on him. That's when Frausto pulled an assault rifle and pointed it at Aispuro. He waited until the two men climbed back into the car before he opened fire, Meza told police.

He tells them about the 1993 hit, telling the cops the dead man was his cousin. He hadn't protected Frausto on a deal so Frausto had him killed, he says.

"He's a very uhm ... He does it his way," Meza told the police. "He does a lot of things his way, and nobody ever knows. Besides, people – they fear him."

By 2004, the Maricopa County Attorney's Office turned down the case. "No reasonable likelihood of conviction because of possible self defense," the cops stated in the report. "The subject has been identified, Antonio Frausto Ocampo, H/M, 4/1/6/64, and this case will be exceptionally cleared."

We'll just keep an eye on this trial and see what happens next.